Making a Custom Mechanical Numpad

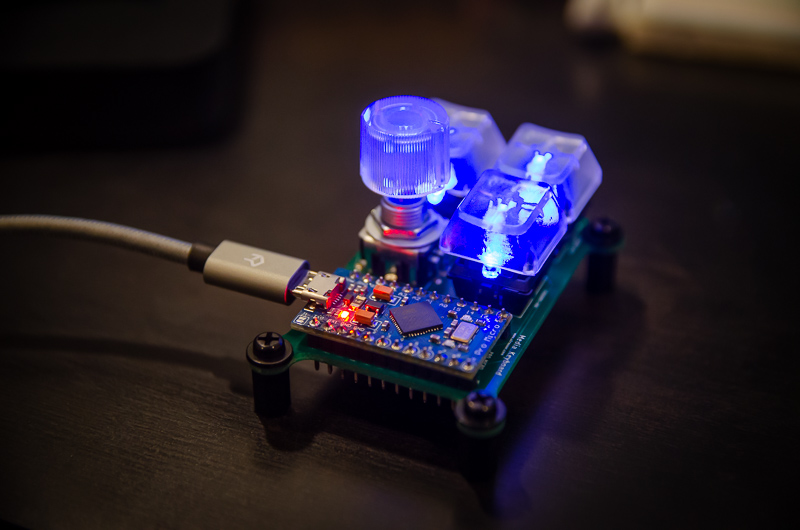

After building a small media keyboard in 2019, I always wanted to go a little bit bigger with respect to custom mechanical keyboards. But instead of going straight from the 3 switches plus the 1 rotary encoder of the 2019 keyboard to a full 104-key project, I opted for a smaller starting point: a numpad with media keys, which will nicely complement my 75% Vortex Race 3 keyboard.

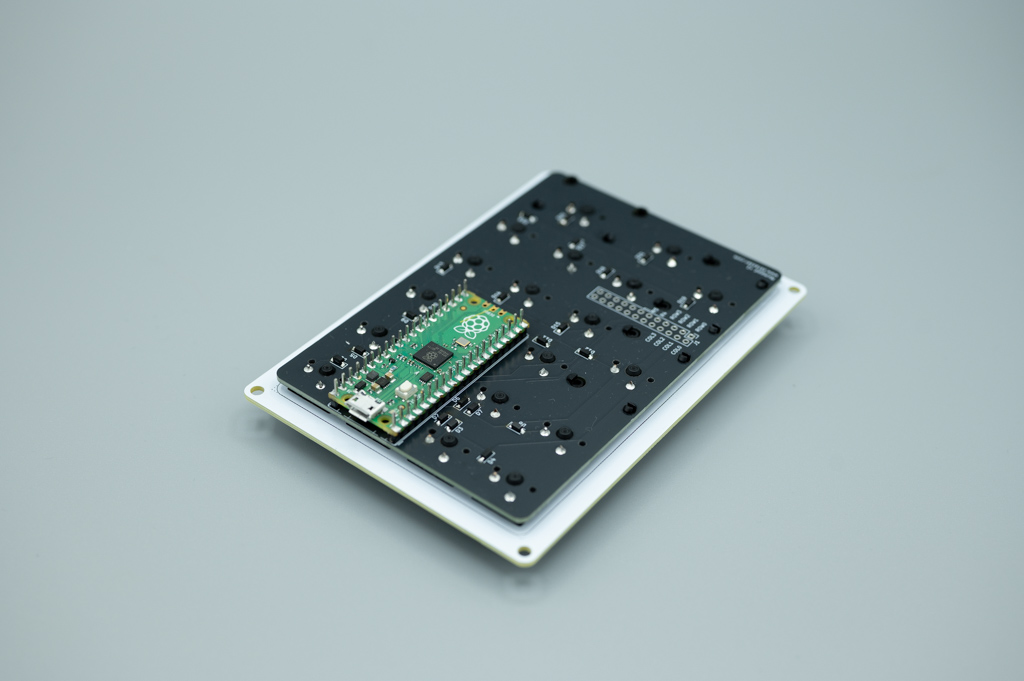

The 2019 project was fairly small in scope. A custom PCB with standoffs held the keys. There was no plate or enclosure. An Arduino Pro Micro ran the firmware that I wrote from scratch. For this version, I am going for a proper setup with plate-mounted switches and an enclosure. For the firmware, I’m using QMK, an open-source firmware that can be quickly adapted to all kinds of keyboards. And for the microcontroller, I am using a significantly more beefy Raspberry Pi Pico.

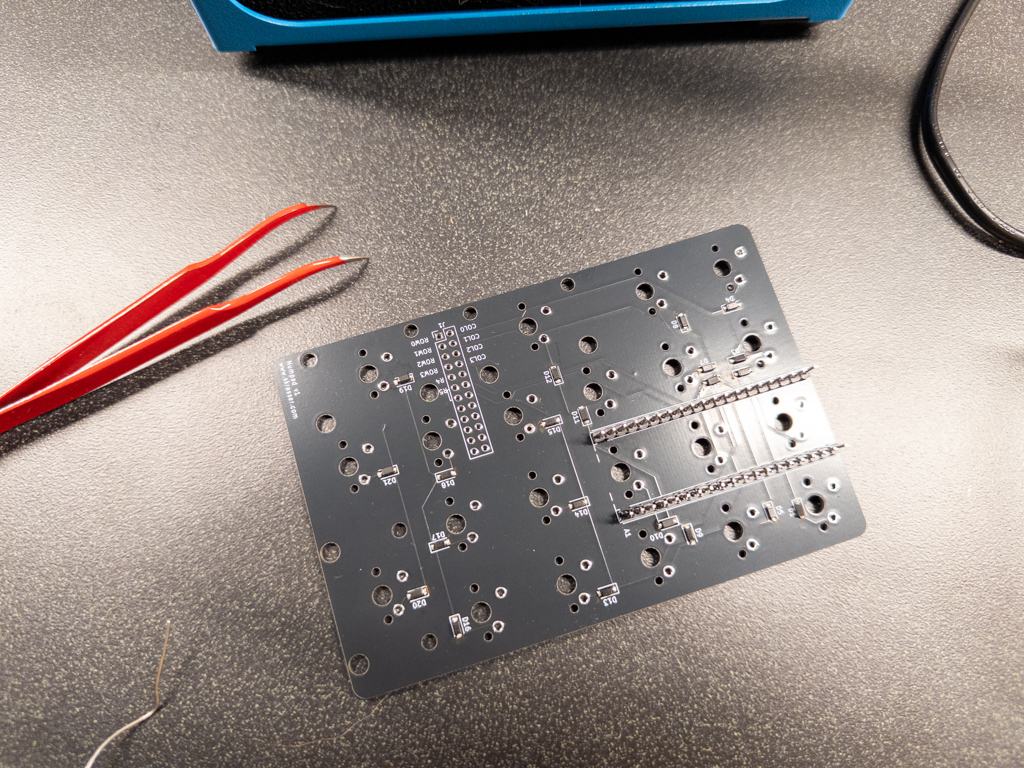

In the 2019 project, all switches were directly wired to GPIO pins on the Arduino board. For this new instantiation, I am using a keyboard matrix. QMK handles scanning it, so there’s no worrying about having to write any extra code. While there would be enough GPIO pins on the Pico for each switch, using a matrix also is good practice for building a larger keyboard in the future. For better or for worse, it also means getting practice soldering 21 tiny surface-mount diodes to the PCB.

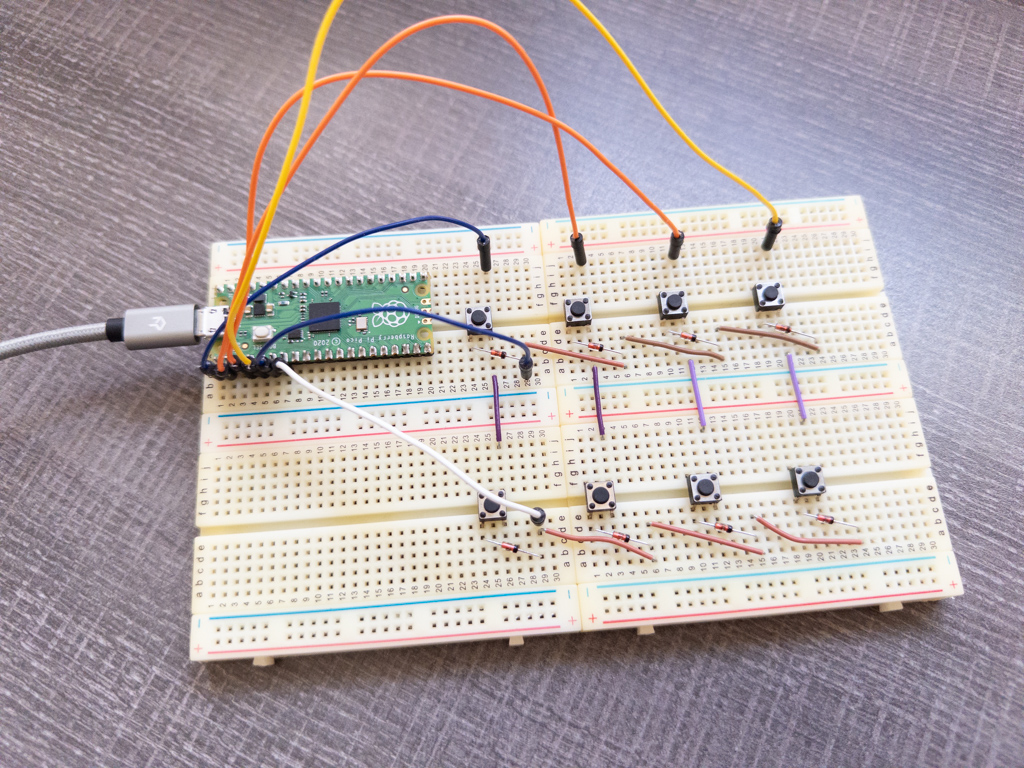

To get started with QMK, I built a quick breadboard prototype with two rows of four keys each. QMK has an already suitable layout for my setup, LAYOUT_numpad_6x4. After configuring QMK and building a custom firmware, installing it on the Pico is actually a very polished procedure: the Pico shows up as a USB drive when ready to program, and one just has to copy the firmware file over to that drive. The Pico then reboots with the new firmware, and the USB drive disappears.

So far so good, but in my case, the USB drive reappeared after programming, indicating that something went wrong. My first suspicion was that the firmware file was corrupted. After some debugging, I came across the real issue. On my breadboard, I wired the pushbutton switches such that the connection is always closed. QMK has a feature called “bootmagic” that puts the microcontroller back into programming mode when the switch in row 0/column 0 is pushed on power-up, which was the case for me. Everything worked as expected after wiring the board correctly.

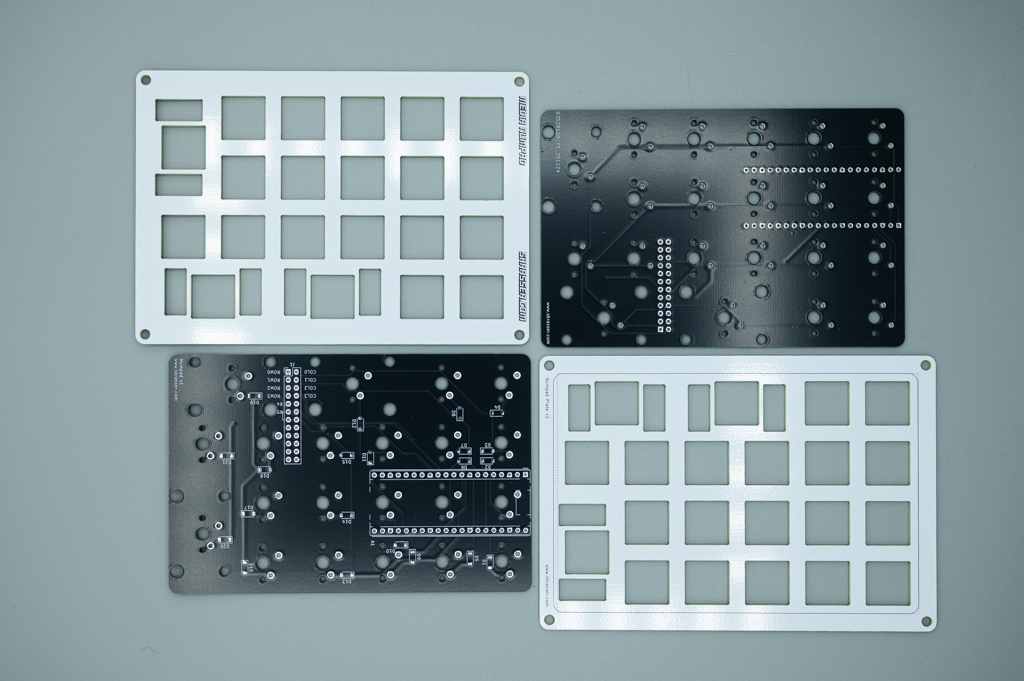

In a plate-mount design, the switches are held in place by a plate. The electrical connections are then handled by a PCB below the plate (or in some designs, the switches are handwired). I created the PCB using KiCad. The Pico mounts to the PCB using pin headers on the underside. There are solder points for switches underneath the Pico, so directly soldering it to the board using its castellated mounting holes was not an option.

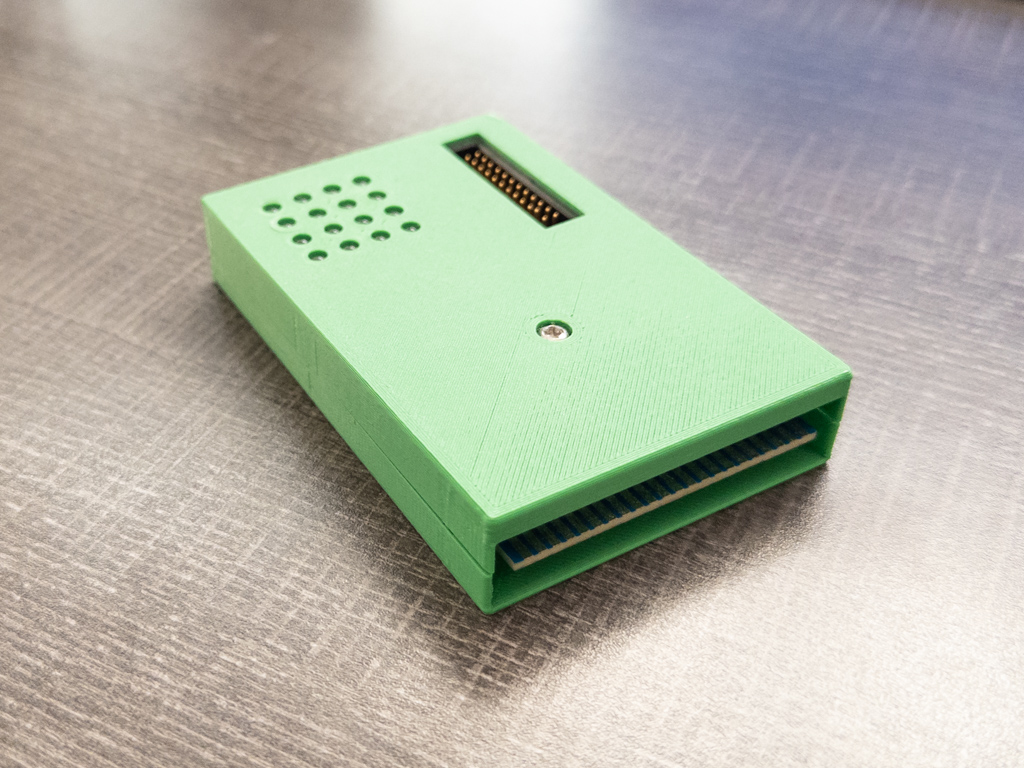

In addition to the Pico, the PCB allows for mounting a pin header that brings out all row and column signals. The pin header is compatible with my Commodore 64 VIA expansion cartridge, which in the interim got a 3D-printed case too (see below). I’m planning on using the pin header for a future project to read out the key matrix using the VIA on the C64.

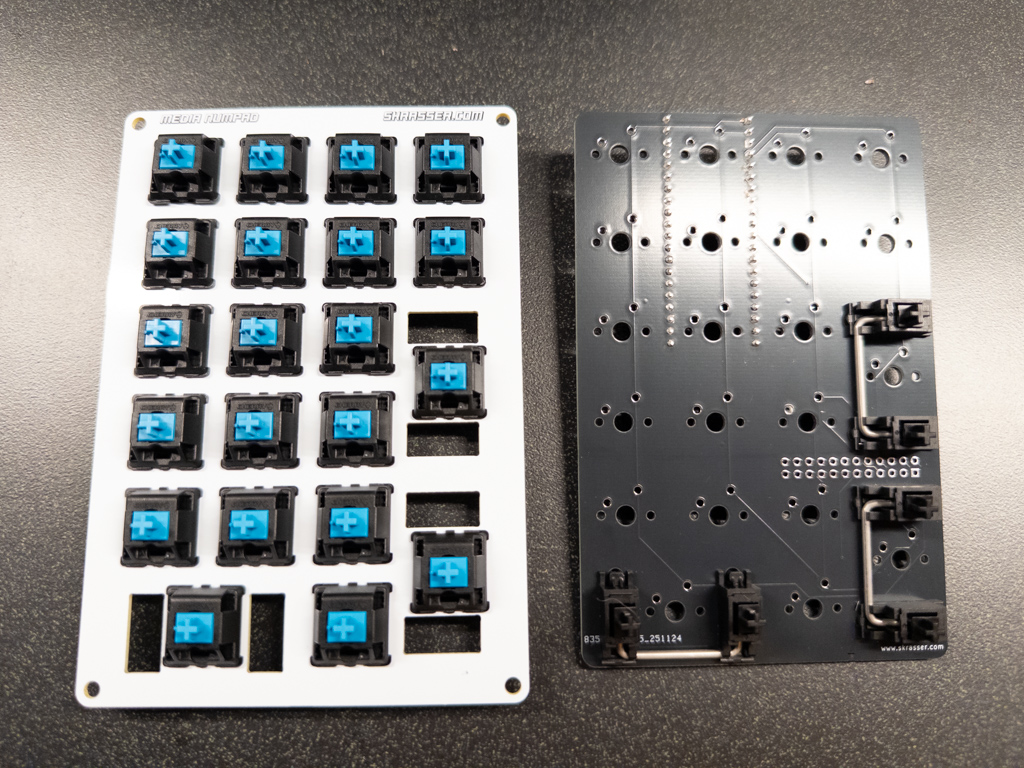

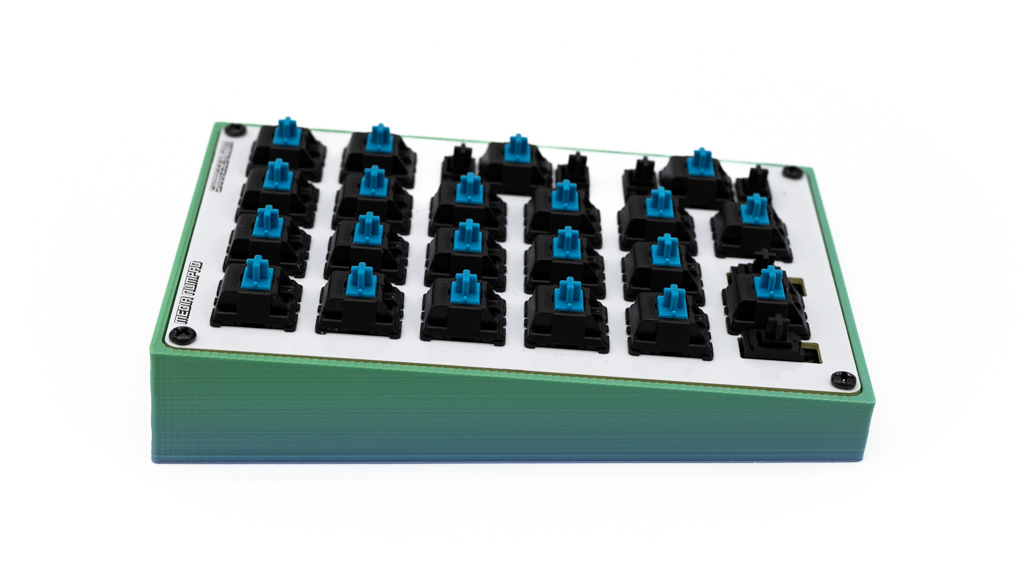

For the plate, I opted to have it fabricated as another PCB, although without any electrical function. I’ve used KiCad for the plate as well. For the openings for the switches, I used the ai03 Plate Generator, a nifty web app that takes a layout and some configuration settings as input and then spits out drawings for the necessary cutouts. I exported the cutouts as a DXF file, which I then imported into KiCad. In KiCad, I added the outer edge of the plate, mounting holes, and some text for the silkscreen.

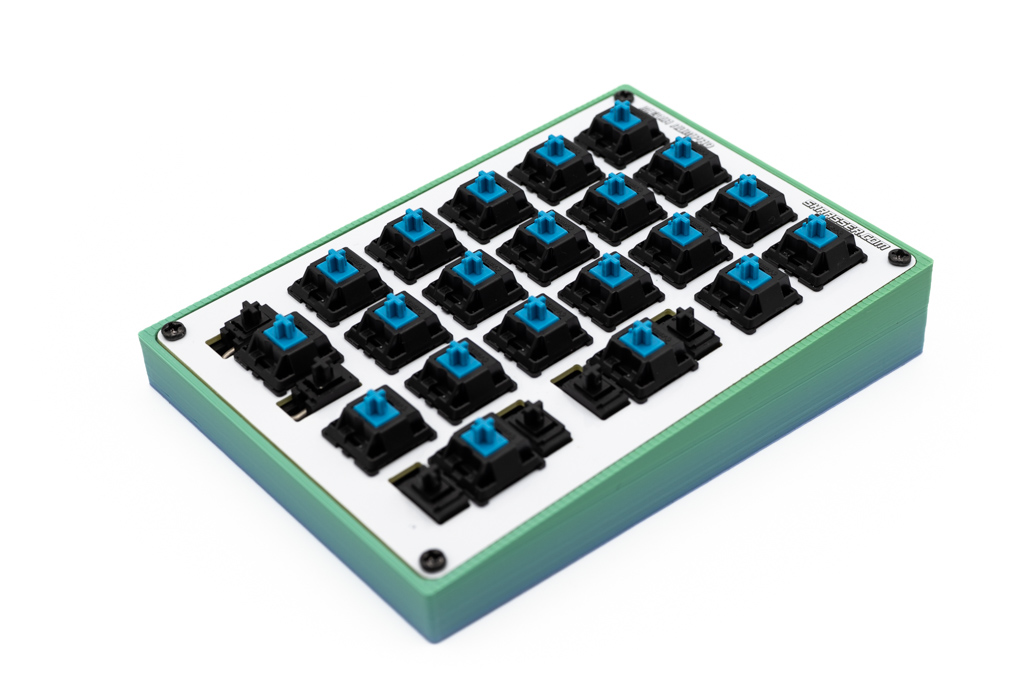

As part of this project, I also wanted to get practice with larger keys. The numpad contains three 2u keys, i.e. keys that are 2 units large, with a unit being the size of a single regular key. The zero key is 2u wide, and both the enter and the plus key are 2u tall. For these keys, stabilizers (“stabs”) are needed so that they do not tilt while being pressed. Stabs can also be plate or PCB-mounted. In my case, I picked PCB mounted ones since that seemed the safest bet for the types of stab cutouts the Plate Generator produced, and the Cherry MX PCB footprints for KiCad already have the right mounting holes for the PCB underneath. As far as parts go, diodes and switches are easy to come by (I got them from Mouser). For the stabs, I got a bunch of 2u PCB-mount ones from Thock King.

The keycaps for the numpad are a custom design I had made by Yuzu Keycaps. Yuzu lets you pick colors and print for each key using a web-based designer. While they support images and icons on keys, I opted for all keys to have text labels. I’ve ordered two sets of keys—the second set for a version for the aforementioned C64 project idea. They’re still in the mail and will hopefully arrive soon.

Assembly of the PCBs was fairly straightforward. I’ve started with the surface-mount diodes. Diode 1 took a few attempts, but by Diode 21 everything went fairly fast. After the diodes, the pin headers for the Pico went on. Those are through-hole parts, so they’re easy to solder. Next, I’ve put the stabs together, which come as separate parts: housings for each side (which snap into the PCB), a stem that goes into the housing, and a wire that connects the stems so they move in unison. The stabs then go into the PCB. After that, I’ve snapped all Cherry MX switches into the plate. After aligning the plate and PCB, I’ve soldered the switches (again, easy since through-hole). After that, the Pico can be soldered onto the headers, covering up the soldering points underneath. Then, plugging the stack of PCBs into my computer and copying the firmware I’ve tested using the breadboard to the Pico makes this contraption officially a keyboard.

Testing all the switches while being connected looked promising but resulted in mild disappointment after arriving at the “9” key. A quick inspection revealed that I missed to solder a few switches. After getting that corrected, everything worked as expected. The design is not great for maintenance, and luckily I did not miss anything covered up by the Pico.

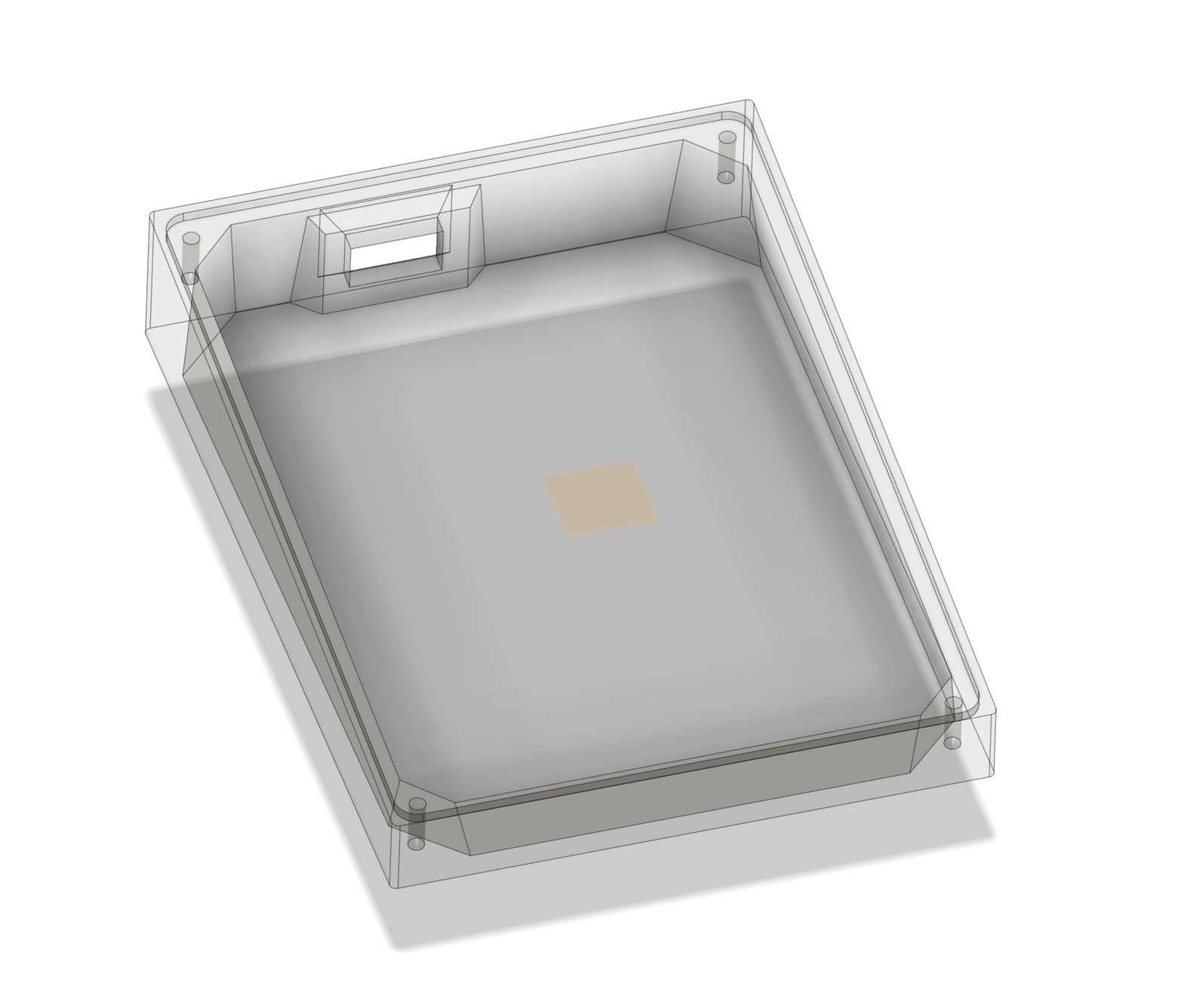

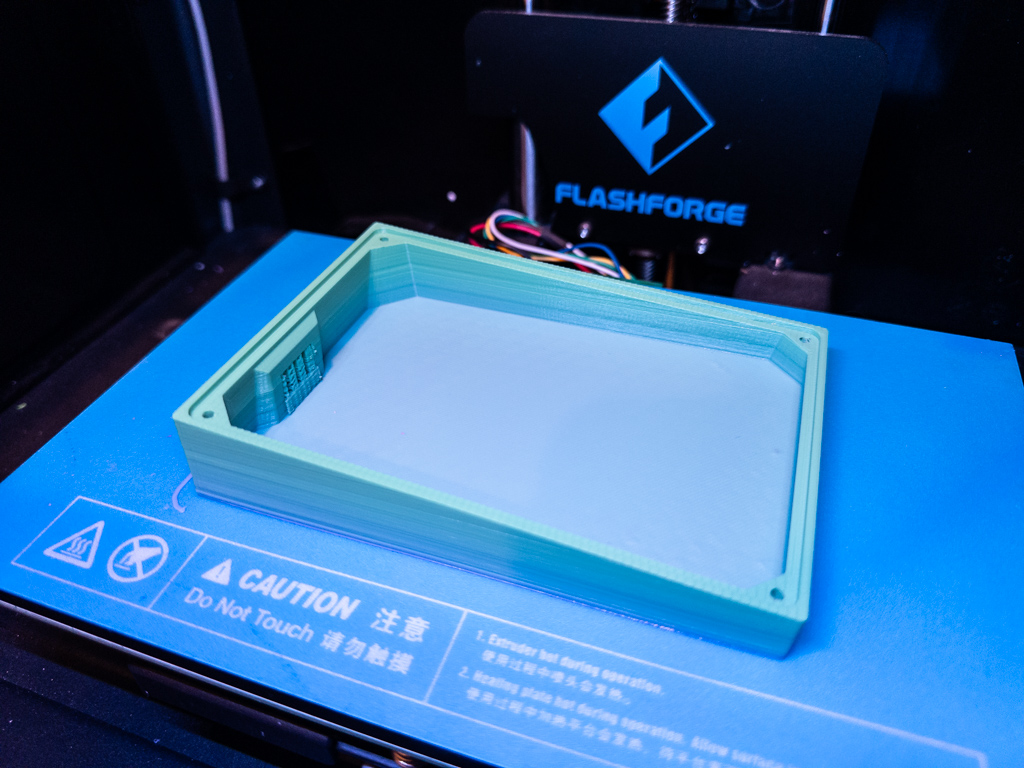

For the enclosure, I decided to give FreeCAD another shot. I tried it out a few years back but didn’t get far back then. There has been some amazing progress with its capabilities, but I ran eventually into issues I wasn’t able to resolve. It still has a number of unintuitive workflows, and it’s not easy to pick up for beginners. Eventually, I’ve reverted back to Fusion.

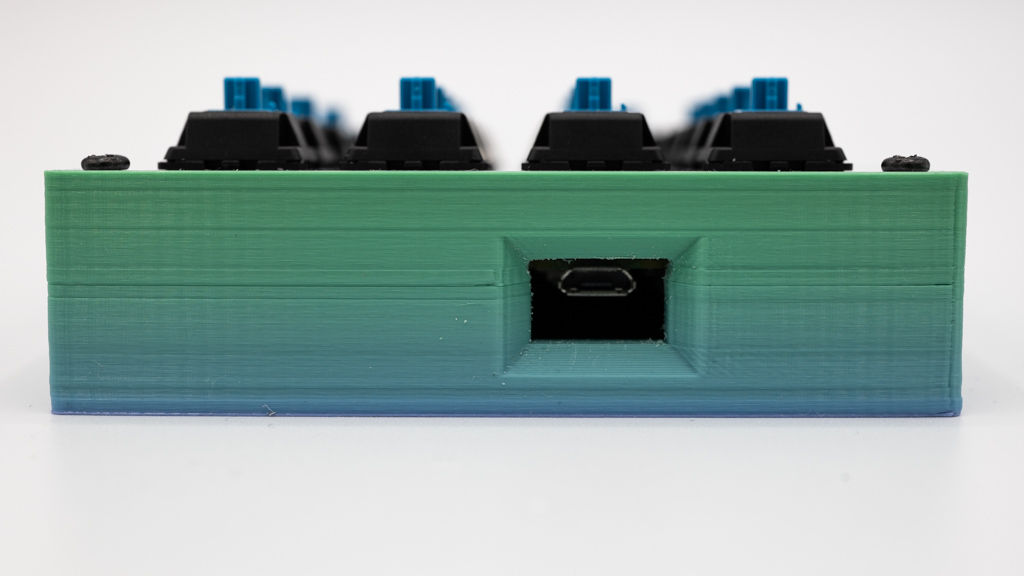

Shannon had some nice looking gradient filament from another project that I decided to use for the enclosure. The print came out alright, but the opening for the USB port was too low. As it turns out, my board stack is thinner than the 3D model I used as reference to design the enclosure. For now, I’ve solved the problem with a file since I don’t want to wait another 5 hours for a new print.

Now all that’s left is to wait for the keycaps to arrive. Hopefully there are no issues with the stabs—those being PCB mounted will make any adjustments complicated. Something to bear in mind for a future design. Below are some shots of the (almost) final result.

Subscribe via RSS